It happened sixty-five years ago, but for me it was just yesterday. From the book.

~ 2 ~ “From the Halls of Montezuma”

~ 2 ~ “From the Halls of Montezuma”

Woody and I eagerly walked into the recruiter’s office in downtown Baltimore the next morning. A Marine sitting at a desk reading a newspaper asked, “What do you kids want?” We told him we wanted to be Marines. He asked why we weren’t in school. We proudly proclaimed, “We quit!” He told us to go finish school then come back to see him after graduation. I’m convinced he was using reverse psychology on us. We literally had to talk him into letting us join.

He told us he might be able to get us in, but it would have to be for four years since we were high school dropouts. So? Anything was better than spending another year in school.

I’m not sure why or when I decided I wanted to be a United States Marine. There were probably several reasons for this choice. One may well have been that I was exposed to the Marines at an early age. My brother-in-law, John, was a career Marine. I spent a few weeks with him and my sister during the summers in the mid-fifties and I particularly remember visiting Quantico, Virginia, when John was a sergeant. His military occupational specialty (MOS) was explosive ordnance disposal (EOD); these are the guys called today when there’s a bomb threat.

While there, I went to work with him on occasion and I’m quite sure these experiences influenced me wanting to be a Marine.

I saw the movie Battle Cry at an early age, but had not yet read the book; heck, at this point in my life I had not read any book. I did read it years later, as it would serve me well due to a strange set of circumstances.

I am sure the uniform also had some influence. I mean, let’s face it, does anybody have a uniform as sharp as Marine dress blues?

To be truthful, the Marine Corps’s reputation for making men out of boys was something I badly needed at the time. At this point in my immature life, I needed the Corps more than it needed me.

Whatever the attraction, I was convinced very early in life that I was going to be a Marine.

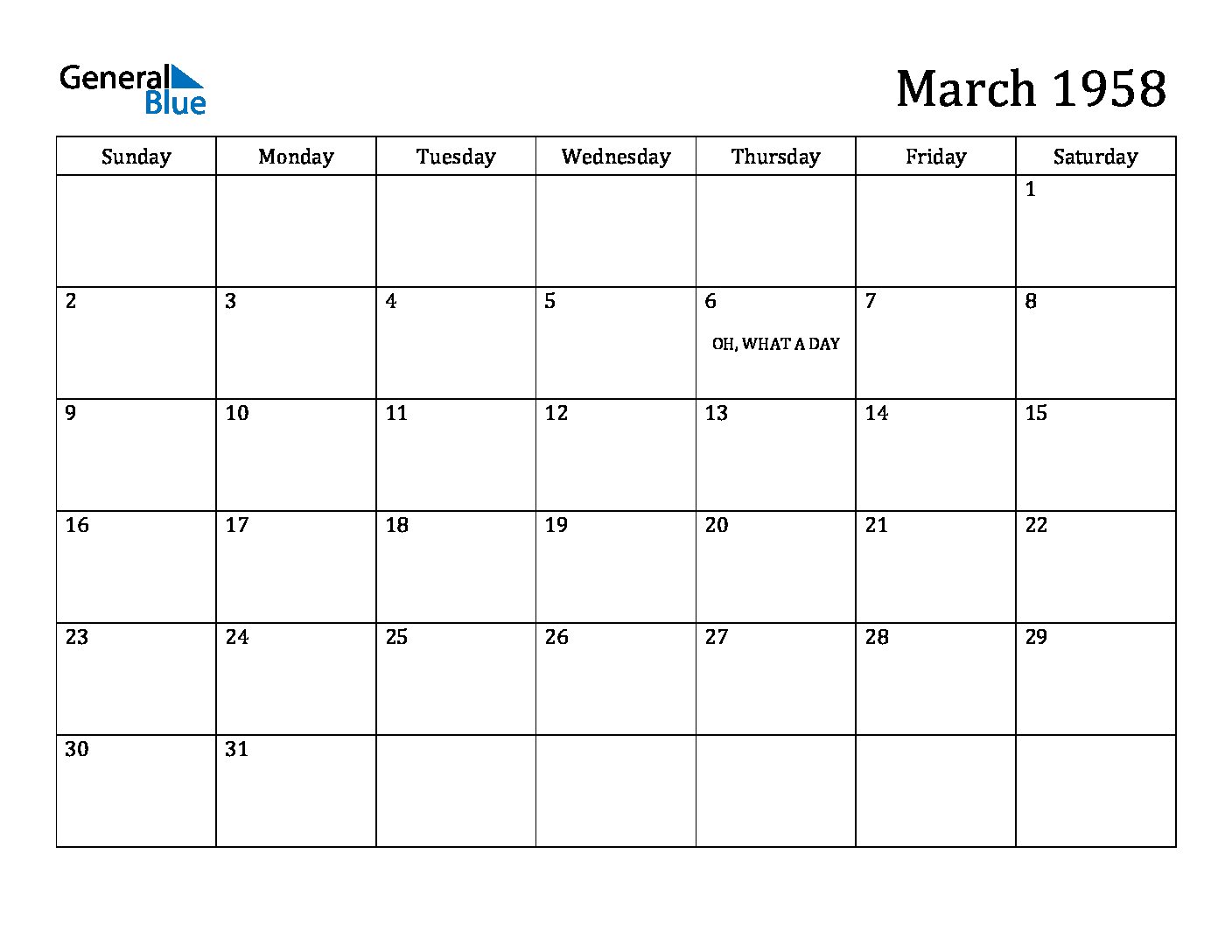

On March 6, 1958, after completing all the paperwork and physicals at Fort Holabird, Maryland, I said goodbye to Mom and Dad. Woody and I then boarded a train at the Baltimore station, along with several others, bound for Parris Island, South Carolina, where the Marine Corps’s East Coast recruit training facility was located. The recruiter entrusted to me a large, sealed manila envelope. I was to deliver it to someone in command when we arrived at our destination. He informed the group that I was in charge—my first responsibility as a future Marine.

The train ride remains a vague memory to me except that we were assigned to a specific car where we were told to remain for the entire trip. I recall that some of the boys brought along a considerable amount of beer smuggled in their baggage, which they shared with some others. I was too nervous to drink. I remember one of the boys boasting as to how he was going to breeze through this training—he wasn’t going to take any guff from the drill sergeants.

With each stop along the way, our car became more crowded with more boys on their way to this infamous place with an exotic-sounding name—Parris Island.

Most of us were asleep when the conductor shouted out that this was our stop—Yemassee, South Carolina. I stepped off the train into total darkness with a cigarette in my mouth. Suddenly it flew off somewhere into space with what I thought were a few of my teeth. This cantankerous fellow, wearing a hat I’d last seen on a bear with a shovel in his paw on U.S. Forest Service posters, was screaming for us to do something. I had no idea then how symbolic that hat was nor that I myself would someday wear it.

Everyone was running in circles, bumping into each other, falling down. The greeting Marine was screaming, “Move! Move! Move!” which we were certainly doing but had no idea where to. I heard someone crying out for his mother. Another boy was screaming for help—surprisingly, he was the one who bragged about not taking any guff from the drill sergeants.

Everyone was running in circles, bumping into each other, falling down. The greeting Marine was screaming, “Move! Move! Move!” which we were certainly doing but had no idea where to. I heard someone crying out for his mother. Another boy was screaming for help—surprisingly, he was the one who bragged about not taking any guff from the drill sergeants.

Absolute chaos ensued. Finally, he pointed to a building. We all ran towards it, jamming the doorway, attempting to get through it and out of the way of this insane person’s wrath.

Inside the building were steel beds stacked two high with a bare mattress lying on them and bright lights in the ceiling with shades hanging over them. The Marine thundered, “Get in a rack!” What the hell is a rack? we wondered. I didn’t recognize anything that might be a rack, so sheer chaos continued as we all tried to figure out what exactly this fellow was directing us to get into.

Finally, some jumped into one of the steel beds whereupon we all followed suit; some beds even had two boys squeezed together. The Marine yelled, “Freeze!” Immediately the room fell into total silence except for the springs of the steel beds squeaking slightly as we all lay very still. He turned out the lights, and slowly paced up and down the center of the room while telling us we were turds, slimy civilian shit. We were in for one hell of a time when morning came, he warned, so we had better get some sleep since it would be the last time sleep would come for the next four months.

Welcome to boot camp!

As I lay there, I could hear the muffled sounds of boys sobbing, probably wondering like the rest of us, What the hell have I gotten myself into?

I don’t know how long I slept or if I even slept at all, but suddenly the lights came on and a loud banging sound awoke everyone as the same Marine was screaming at us to stand in front of our racks. The large metal trash can he’d thrown was still rolling around the floor as we scrambled from our supremely uncomfortable beds—now to be known as “racks.” We were then herded outside onto a greyhound-type bus. I had no idea of the time except it was pitch black and cold.

As I was boarding the bus, I remembered the manila envelope still lying on my rack. My first responsibility as a Marine and I’d blown it. I really did not want to approach this crazed Marine, but I had to retrieve that envelope. I reluctantly began, “Mr., I need to go back into the building to—” I never finished the sentence. He was screaming and spitting saliva in my face. I had no idea what he was saying, but I sure wasn’t going to ask him to repeat it. He shoved me towards the building. I ran in, grabbed the envelope, and bolted back outside.

By the time I returned to the bus, I was the last one to board there by forcing me to sit next to the ill-tempered, Smokey Bear-hatted Marine. I developed goose bumps as I took my seat, so close to this fearsome devil that I was expecting him to chew my head off just for kicks.

I distinctly remember the bus passing through a gate and seeing the Marine sentry smiling as we drove past. Other than swamps on both sides of the road, I could see nothing out the window, nothing that gave a hint of civilization.

We finally came to some buildings whereupon we were herded off the bus into a classroom filled with school chairs, the types that have a small desk attached to them. There were other Marines waiting there for us.

After much shouting for us to find a seat and sit our slimy civilian asses in it, we were required to fill out a postcard addressed to our parents. We were told to write to them that we arrived safe and would write again later. Then they hurried us into another part of the building where we went through a line holding a metal tray out in front of us while someone piled food onto it. We ate in total silence. When we finished—mind you, this was not as leisurely a breakfast as we were accustomed to at home—we were herded back into the classroom. The sun was just rising on our first morning as recruits—literally as well as symbolically.

Oh what a day it was!